Anyone who is familiar with object-oriented programming, knows its various concepts like inheritance, abstraction, encapsulation, etc. and how powerful they are in writing structured code to solve problems. But as the code base becomes more and more complex it becomes more and more difficult to maintain and extend. Consider the below class:

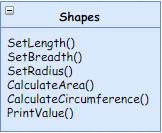

Here, a class Shapes is trying to represent different shapes, calculate different properties, etc. Although simple, we can see the type of complexity and maintenance issues this will cause once the number of shapes handled by the class starts increasing.

To prevent code from getting into such pitfalls, various methodologies were created which include SOLID which

is a mnemonic acronym introduced by Michael Feathers for the “first five principles” named by Robert C. Martin in the early 2000s that stands for five basic principles of object-oriented programming and design. The intention is that these principles, when applied together, will make it more likely that a programmer will create a system that is easy to maintain and extend over time. – Wikipedia

- S – Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O – Open/ Closed Principle (OCP)

- L – Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I – Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D – Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Let’s have a look at each of these in some detail.

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The single responsibility principle states that every module or class should have responsibility over a single part of the functionality provided by the software, and that responsibility should be entirely encapsulated by the class. All its services should be narrowly aligned with that responsibility. – Wikipedia

Or in Robert C. Martin’s words

A class should have only one reason to change.

As depicted above, our class Shapes is trying to do a lot of things and it is easy to see that it has multiple responsibilities. Lets apply the SRP to Shapes.

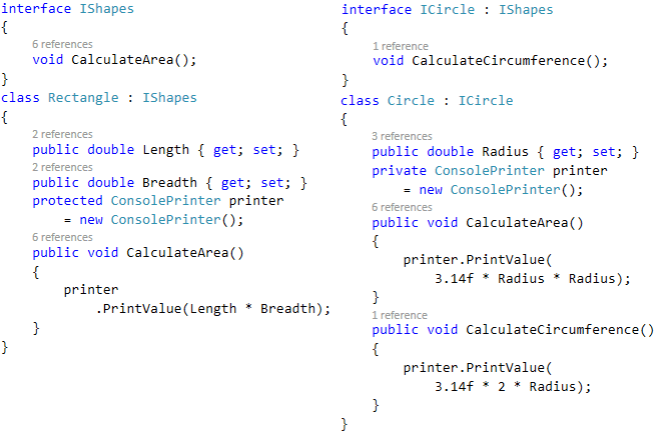

The class diagram depicts the scenario after applying SRP. Our Shapes class was handling all shapes as well as printing. Now, we created an IShapes interface that defines the operations a shape must perform and it is implemented by individual shape classes. So now, class Circle is responsible for representing only a circle and its operations. Thus, the only reason for a Circle class to change is for any change related to a circle. Same is true for classes Triangle, Rectangle and any other shape class that may be added subsequently. Also, printing a value is not a responsibility of a shape class and can be given to a separate ConsolePrinter class, to print the values on console. Lets have a look at the code. The IShapes interface and class ConsolePrinter are below:

Note: The class diagram depicts the high level type structures and their associations, whereas code is their detailed implementation. So there might be a mismatch between methods/ fields mentioned in class diagram and actual code.

Thus, by applying SRP, we define types which encapsulate only functionality and are responsible for only that functionality.

Open/ Closed Principle (OCP)

The open/closed principle states “software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification”; that is, such an entity can allow its behaviour to be extended without modifying its source code. – Wikipedia

Consider our Shapes class. Assume that it is designed to handle circles, triangles and rectangles. Now, suppose we want to add functionality for a pentagon. Now, to accommodate this requirement, we will have to modify our Shapes class and add fields, methods to handle pentagons. We can imagine how difficult it will be if we have to modify the Shapes class for every new shape we want to add. It is possible that the Shapes class does not even belong to the client application but is a packaged library. To handle such scenarios we can design our Shapes class to be closed to modification, i.e. no new functionality can be added to Shapes, but open to extension, i.e. the behaviour of Shapes can be extended by other classes.

This looks like a perfect case for inheritance, doesn’t it? It is. But typically, the base type is an abstract type (interface/ abstract class) which defines the operations that can have multiple implementations and each of these implementations can be substituted for the base type (polymorphism).

In our shapes example, initially we had a single class Shapes, to which we applied SRP and created separate classes for each shape and printing. But, there is one more important thing that we did here. We created an abstract type IShapes an interface, which define the operations and is extended by every shape class. Now if we add a new shape, say Pentagon, we do not need to modify IShapes, but Pentoagon can implement it and extend its functionality.

Consider the method CalculateArea from the original Shapes class and the client code as shown below:

As we can see, for every new shape that our application may handle, we will have to modify Shapes class and add a new case to CalculateArea, also may be some properties to define the shape. Now, please go through the IShapes interface and CalculateArea method implementation of classes Circle, Rectangle, Triangle, as show above (SRP section). Have a look at the below client code after applying OCP.

So as we can see, we can extend the functionality of IShapes in any way we want and use the derived types in place of each other polymorphically, thus adhering to OCP.

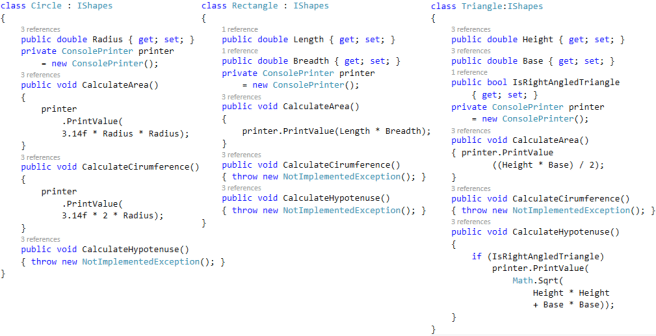

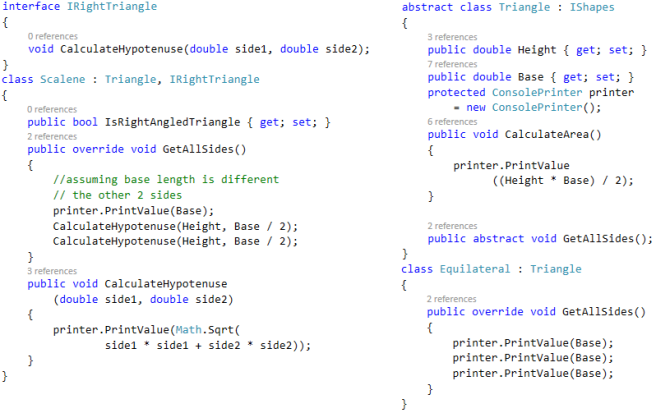

To understand better, lets consider a case where we mark our Triangle class as abstract and add an abstract method, GetAllSides to it. Also we add 2 new types of triangles, Equilateral and Scalene, which extend Triangle.

The code looks like below:

So, we can extend the Triangle class as it is open for extension, but we need not modify it and keep it closed for modification. The code is not very beautiful and calculating hypotenuse is too much of a trouble, but CalculateHypotenuse comes from the original Shapes class where it was right angled triangle specific. We will come to it.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Liskov substitution principle was given by Barbara Liskov and it states

Let

be a property provable about objects

of type T. Then

should be true for objects

of type S where S is a subtype of T. – Wikipedia

What this means is that every subclass/derived class should be substitutable for their base/parent class. And this substitution should be complete, i.e. no functionality or invariant of the base class should be broken. Invariants can be assumptions of behaviour by clients, or any preconditions or post-conditions. A client should not know the actual type of the object it is using, and use an object of derived type in the same way it would use an object of base class.

Here, the key concept is Substitutability.

When we look at inheritance of a base class by derived class, we define it with “is-a” relationship. For e.g, a car is-a vehicle, a triangle is-a shape, etc. But what LSP states is that the relationship between a base and a derived class must be “is-substitutable-for”. So, when we derive a class Car from a base class Vehicle, we must check if, with our implementation, Car is-substitutable-for Vehicle.

Lets try to further understand LSP with our shapes example. Now, we know that square is a type of rectangle and so we can say that square is-a rectangle and add a class Square that derives from our Rectangle class.

The class diagram shows a class Square that derives from Rectangle. Now, let us look at the code for class Square and client code and results for different scenarios.

We made the following changes to our Rectangle class:

- Changed visibility of printer from private to protected to make it accessible to Square.

- Marked Length as virtual to override in Square. We don’t require both Length and Breadth in Square as both must be equal.

- Marked method CalculateArea as virtual to override in Square.

Lets go through the scenarios in the client code:

- l = 3, b = 2 – Here we initialise rectangle as a new Rectangle & get the expected result 6

- l = 3, b = 3 – Here we initialise rectangle as a new Square & get the expected result 9

- l = 3, b = 4 – Here we initialise rectangle as a new Square & get the result 9 instead of the expected result 12.

So, if both the second and third scenarios uses an object of type Square, why is the behaviour different? Actually the behaviour is not different. As we can see, the CalculateArea method of Square uses only Length to calculate the area as for a square l = b. So, even if we set the value for Breadth, Square ignores it. Now, scenario 2 works as we are setting both Length and Breadth as 3. So the rectangle we are trying to create with a Square object is actually a square (l = b). Whereas in scenario 3 we are initialising a rectangle that is not a square (l = 3, b = 4) as an object of type Square. So we are essentially substituting the class Rectangle with Square, as Square inherits (is-a) Rectangle, and calling the CalculateArea method of Square expecting it should work for Rectangle and it does not.

So, as per the Liskov Substitution Principle, if we want to add a class for square to our application, it should not derive from Rectangle but from the interface IShapes (OCP).

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The interface-segregation principle states that no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use. – Wikipedia

Here interface does not necessarily mean an interface denoted by the C# keyword of the same name. It can be anything, an actual interface or a class. The important thing to note here is that a client should not need to depend on methods it does not use. So,

- if a class implements methods all of which are not necessary for each type of client,

- if a class implements an interface and has empty methods (our case),

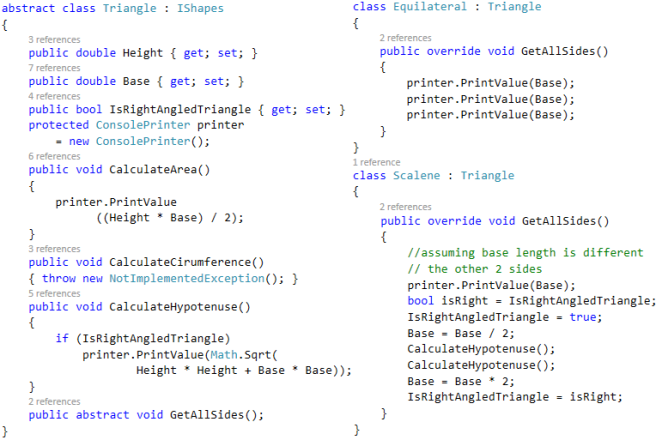

it can be a case for applying ISP. Lets look at a portion of class diagram of our revised shapes application.

As we can see here, IShapes define 3 methods which are implemented by Circle, Triangle, Rectangle. Well, but do each of these classes actually implement all the methods? If we revisit the code in the SRP section, we can see that only the method CalculateArea has actual implementation in all the 3 classes whereas Rectangle and Triangle has no implementation for CalculateCircumference and Circle and Rectangle has no implementation for CalculateHypotenuse. Now imagine if a client instantiates an object of Rectangle; the object will have method CalculateCircumference, which neither the client is expecting nor will ever use for a rectangle.

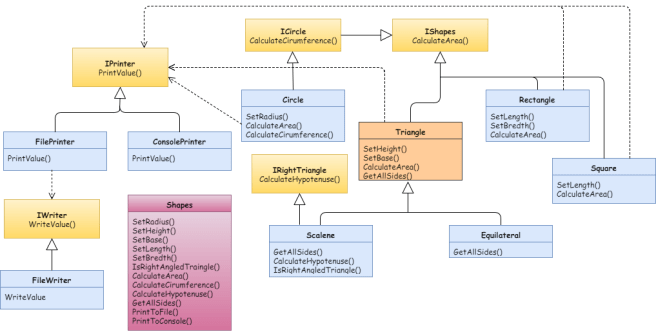

So lets apply interface segregation principle to our application and look at the resultant class diagram.

Below is a description of the changes we did applying ISP:

- Any shape should have the ability to calculate its area and so the only method defined by IShapes is CalculateArea.

- In our example, only a circle can have circumference. So we moved the method to ICircle, which implements IShapes. Circle class implements ICircle.

- Rectangle implements IShapes and no longer needs to have empty implementations for CalculateCircumference and CalculateHypotenuse.

- When discussing open closed principle, we marked Triangle as abstract and derived Scalene and Equilateral from it. Now, we need to remove CalculateHypotenuse from IShapes but we can’t put it in Triangle as Equilateral triangle can never be right angled. So we define a new interface IRightTriangle which defines CalculateHypotenuse and is implemented by only Scalene. Similarly, if we add a class for isosceles triangles, it can implement IRightTriangle as an isosceles triangle can be right angled.

Thus, ISP helps in defining classes and interfaces which are concise and provide only the functionality that is expected of them. Below is the refactored code for the affected classes and interfaces.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

The dependency inversion principle states:

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions. – Wikipedia

When we say dependency, it can be of many types in an application. e.g. framework, OS resources, web services, external libraries, types.

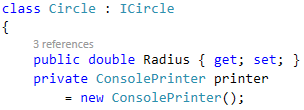

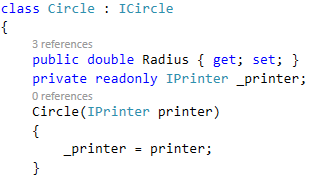

For our discussion we will consider dependency between types. Lets take the relevant section of class Circle and see how our shape classes are dependent on ConsolePrinter.

We are instantiating an object of ConsolePrinter in Circle and using the object printer to print values to console. Now, suppose we have a new type of printer class, FilePrinter, which prints values to a file. Now, instead of ConsolePrinter we want to use FilePrinter in Circle or any other class. So what will we do? Well, we can just change the printer type to FilePrinter or have objects for both the printer classes and pass a parameter to methods to tell which printer to use. Both these approaches work but below are some of the issues:

- Every time we change or add a type of printer we will have to change the code of Circle class. This violates the open/ closed principle. Ours is a small example, but imagine doing this for large eCommerce site which is already in production or what if the application using our Circle class has no access to the source code of Circle.

- Also, Circle class has an additional responsibility of instantiating printer objects. This violates the single responsibility principle.

In fact, the best way to detect a dependency is to see if :

- new keyword is used

- static methods are used, which may be accessing any other resource (e.g. database)

To overcome these shortcomings in our shapes application, we need to:

- Create an abstract type (interface IPrinter) and put the dependencies in it. In our case the method PrintValue.

- Derive concrete classes from this interface. In our case classes ConsolePrinter and FilePrinter will implement the new interface IPrinter.

- Inject the interface in dependent classes. In our cases IPrinter will be injected into classes Circle, Triangle and Rectangle.

The section of our class diagram after applying DIP looks like below:

As we can see here, our FilePrinter class depends on IWriter and FileWriter implements IWriter and writes value to a local file. This is helpful in a scenario where suppose the location of file changes from local to a blob or some remote location (ftp). Here we can see all the SOLID principles in play.

And the code changes to our Circle (also Triangle and Rectangle) class are as below:

Now, neither our Circle class is dependent on ConsolePrinter nor does it have the responsibility of creating a printer class object. Instead Circle is now dependent on an abstract type IPrinter. In fact Circle does not even need to know what type of concrete implementation of IPrinter it will use. This is what DIP says.

To inject the IPrinter dependency, we have declared a private variable of type IPrinter and set it to the parameter of type IPrinter in the Circle class constructor. One more way of injecting the dependency can be to have a public property for IPrinter, which the client/ using class code can set. This will be alright if having an instantiated object for IPrinter is not a requirement for using Circle, but in our case, a valid printer object is must before calling any of the Circle methods. So we inject it using the constructor. Also, it is always a good practice to have all the dependencies for a class instantiated while it is being constructed.

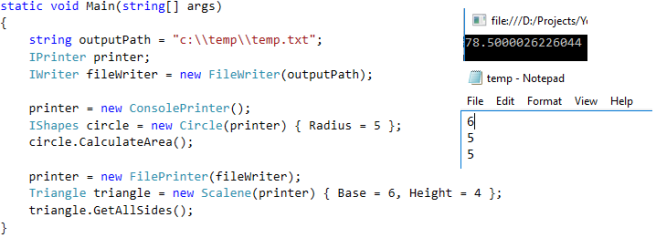

Now our client code, method main in our case, can use the shapes classes like below:

So, now we have applied DIP, but then the question arises where do we insert the dependencies? Well we can do it :

- At application start or some central place which can drive the application like main method in our case.

- Using IoC containers like Ninject, Unity, Autofac, etc. (out of scope of this post)

Conclusion

We have seen how we can use SOLID principles to design a very maintainable, extensible and testable application. All these concepts may seem a bit difficult at start, but are very simple if you try to understand them using an example. Once understood, they are sure to be part of every class that you design or code.

Below is the class diagram of our original Shapes class and of our application after applying SOLID principles.

If you are interested in the final code of the application, you can find it in my Github.

Note: Class diagrams in this post are used to represent the relationships between types and possible method definitions. So the type implementations in actual code may differ from those in class diagrams.